Privacy-enhancing tech and data pooling—a new way to turn the tide on financial crime

Technological innovations have given some players cause to hope that cross-institutional data sharing could become a reality in spite of concerns around data protection.

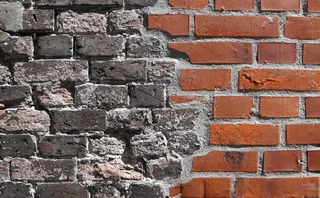

A visitor perusing the fifth floor of France’s Centre Pompidou will encounter two very different compositions in short succession. Wassily Kandinsky’s Picture with a Black Arch is a hodgepodge of lurid blotches and angular black streaks, now recognized as one of the first fully abstract paintings to come out of Europe. Nearby hangs Marc Chagall’s The Wedding. Painted in 1912—just like Picture with a Black Arch—it depicts the Russian Empire where both artists were born. But whereas Kandinsky’s disparate shapes stubbornly refuse to resolve themselves into a recognizable image, Chagall arranges his multicolored stripes and blocks to form people, houses, and a lively village scene.

Anti-money laundering (AML) operations may seem far removed from the glamour of modern art, but Vadim Sobolevski, co-founder of transaction monitoring platform provider FutureFlow, sees the industry’s efforts to combat financial crime through the prism of these two great painters.

“My partner likes to call the two approaches to transaction monitoring Kandinsky versus Chagall,” he explains. “If we look with a human eye on a network that consists of five nodes with basic connections between them, that’s just not very interesting. But if you look at a network that consists of 5,000 nodes, with a lot of circular flow, a lot of interrelationships, and a lot of money coming in and out, that is an interesting pattern. We normally only see the tip of the iceberg.”

As it stands, most AML operations around the world fall firmly in the Kandinsky camp. Financial institutions look for anomalies in their own, narrow transactional dataset: benchmarking an individual’s behavior against themselves, against their user group, or against an institution’s entire customer portfolio. But without an understanding of where that money goes when it leaves their institution, AML officers can often only see a close-up set of truncated shapes.

In recent years, technological developments have laid the foundations for a second method, which vendors hope could persuade banks to pool their data together and see vast webs of transactions stretching across entire jurisdictions. Privacy-enhancing technologies—otherwise known as PETs—allow users to contribute and analyze their data in an encrypted environment, designed to assuage fears that their sensitive information could be identified by each other or obtained by hackers. With the cross-institutional collaboration enabled by this technology, AML officers could pick up suspicious transactions not only between accounts, but between banks, and possibly even across borders.

The technology that may one day enable large-scale transactional data pooling by financial institutions is still in its infancy. Only a handful of startups and consortiums are working on PETs with the intention of creating unified transactional datasets to fight financial crime, and real-life results are still a few years away, at best. If they managed to persuade banks to disclose their fiercely guarded transactional records, PET providers would then have to navigate thorny regulatory obstacles surrounding the use of client data.

Nonetheless, some trailblazers are operating in this area. FutureFlow’s partner, PET startup Secretarium, has developed a technology that acts as a two-way encryption/decryption box, allowing participating banks to contribute information into a fully encrypted dataset via Intel’s SGX Chip, which is a US Department of Defense standard.

Secretarium has already built two apps, Datalign and Semaphore, designed to enable the Societe Generale-led consortium Danie to reconcile reference data without breaching client confidentiality. Now, it hopes to create an encrypted dataset that enables banks to anonymously reconcile transactional data and crack down on suspicious flows of money between firms, too.

Once the data has been contributed by financial institutions, Secretarium harmonizes and then obfuscates it to produce a fully pseudonymized dataset. Then FutureFlow transforms that information into visual network elements that illustrate the flow of money in the financial network—often as much as hundreds of millions or billions of transactions at any given time. Machine learning algorithms processes the elements, searching for a topology redolent of money laundering schemes, and alerts the relevant banks if it finds a potentially suspicious transaction.

Banks spend billions every year trying to improve their AML efforts, while also facing similarly hefty fines for not identifying financial crimes effectively enough. Currently, around 95% of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) raised by banks are false positives, meaning that a good deal of wasted effort goes into investigating and closing potential money laundering cases.

The bird’s-eye view of the banking system offered by pooled transactional datasets could help cut out the noise of false positives, helping to train AIs to distinguish a real suspicious transaction from a false alarm with greater accuracy.

“Our technology essentially allows you to ignore 99% of your analysis, and to simply focus on the things that have been found interesting automatically by the software itself, which it’s quite good at doing,” Sobolevski says.

First steps

PETs currently under development include homomorphic encryption, secure enclave technology, and secure multiparty computation—all of which have been used in some form or another for data sharing between financial institutions. Each has its downsides. Homomorphic encryption, for example, is considered very secure, but it can still take seconds to perform simple computations. Multiparty computation, meanwhile, comes with relatively high costs for servers and communication devices.

In many ways, the PET layer is the first important step. It creates a level playing field, and gives firms the confidence that they can then share information to gather insights

Mark Davies, Element22

But pooling transactional data could come with big gains. Sources told WatersTechnology that a typical bank may only be aware of around 5% of the financial crime that takes place in the institution. A more complete view of inter-bank transactions has the potential to reveal expansive illicit schemes and recoup some of the $2 trillion that may be laundered in the world each year, according to estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

“In many ways, the PET layer is the first important step,” says Mark Davies, a partner at consultancy Element22 in London. “It creates a level playing field, and gives firms the confidence that they can then share information to gather insights. Once the firms are happy with the controls and the security in place, the number of options to reconcile data is huge. I could easily imagine a hundred different applications across an organization: legal information, KYC, AML, transaction monitoring—the list goes on.”

The first hurdle is getting banks to agree. Financial institutions are notoriously protective of their data, and reticence over the danger of disclosing sensitive information trumps even the tantalizing prospect of saving millions on AML procedures. This caution is exacerbated by concerns that being the first mover in an unsuccessful effort could lead to significant reputational damage.

Nonetheless, some banks have taken cautious first steps towards pooling transactional or other data with the intention of identifying potential financial crimes.

The most notable example comes from the Netherlands, where a consortium of five banks, known as Transactie Monitoring Nederland (TMNL), formed in July 2020. Members of the initiative have agreed to pool their transaction data, pseudonymizing any information that could be linked back to individual entities. The data is then crunched by TMNL, which searches for potentially unusual patterns of transactions and sends alerts to the banks concerned. The project is still young, but testing in a proof of concept has suggested that the service can spot suspicious multibank transactional patterns, helping to expose complex schemes that a single bank could not identify alone.

Budding public–private partnerships are also enabling financial institutions and regulators to share best practices and help construct a digital fingerprint of criminal activity. These include Singapore’s AML/CFT Industry Partnership, Lithuania’s Center of Excellence in AML, and the UK’s Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce. In Singapore, public-private collaboration on priority investigations have already led to successful interceptions in excess of $50 million.

For many in the industry, these examples, however nascent, provide hope for the future. “Suppose Singapore—one of the most important financial services hubs in the Asia-Pacific region—succeeds. In that case, there will be a lot of pressure on all sides to achieve a similar arrangement,” says Francisco Mainez, a senior official at AML compliance platform provider Lucinity.

The reality is that the bad guys share data, and they also know that financial institutions don’t share data. That creates a huge gap

Francisco Mainez, Lucinity

Lucinity uses augmented intelligence to display compliance data in context, so that officials fighting financial crime can see transaction monitoring, actor intelligence, and SARs all in one place. Mainez says he believes the future of AML lies in a collaborative approach. “The solution is a combination of a data-sharing framework between financial institutions, states, and law enforcement, using vendors as the glue that holds those parties together, and embracing advanced analytics solutions,” he says.

“The reality is that the bad guys share data, and they also know that financial institutions don’t share data. That creates a huge gap,” Mainez adds.

Legal hurdles

The idea of sharing data for the purpose of fighting financial crime is not a new one, but a set of intractable paradoxes have kept this enticing possibility from being realized.

Many jurisdictions have legislation stating that pre-suspicious data cannot be legally shared by financial institutions. Data protection laws like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) say that firms have to believe there is a legitimate interest before they can share any sensitive data.

But without sharing and analyzing all their transactional information, banks only have their own siloed data from which to draw conclusions. This means they are less likely to spot suspicious transactions in the first place, and will therefore have fewer opportunities to disclose information within the confines of the law. It’s a closed system.

“When we talk to banks today, they don’t know if they’re allowed to share data,” Davies says. “They have to go back to their legal teams and get confirmation. ‘Can we participate in this PoC? Can we push our data, even anonymously, into locations where reconciliations can happen?’”

In those specific pockets where suspicion has been raised and perhaps validated by the participating banks, that opens up a way for a separate legal basis for processing, which is now compliance with law

Vadim Sobolevski, FutureFlow

But here, too, FutureFlow and Secretarium believe that they may have a workaround. Because the technology doesn’t need to see the names or addresses of the account holders, it can generate candidates for further investigation without breaching data protection guidelines. In 2020, FutureFlow completed a sandbox with the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) in the UK to explore how the platform could process shared data in compliance with data protection legislation.

The technology sees the strict minimum of data needed to draw conclusions about potential suspicious transactions, and then Secretarium’s platform re-maps the pseudonymized data onto the banks’ original data in order to send suspicion reports to the institutions in question. In other words, the technology that Secretarium and FutureFlow have developed helps data controllers to generate suspicion (which is a legal basis for sharing data and investigating a case) without first exposing sensitive information about their clients.

“The ICO has helped us to generate a two-tier regulatory architecture whereby banks essentially submit their data in bulk for analysis by this utility without having any suspicion,” Sobolevski says. “The legal basis for processing this is not compliance with law, but legitimate interest. … The data is really heavily obfuscated before it’s analyzed. But in those specific pockets where suspicion has been raised and perhaps validated by the participating banks, that opens up a way for a separate legal basis for processing, which is now compliance with law.”

Enter: the regulators

In the face of hesitancy from banks and the rigors of data protection legislation, technology players and industry groups are doing their best to make data sharing a reality. Cyber intelligence sharing community FS-ISAC now consists of more than 5,000 firms around the world that agree to exchange cyber threat information to better understand their exposure.

“Most financial services firms realize the value of threat information sharing as a means to better identify patterns that they otherwise wouldn’t see. The best defense is a good offense, which information sharing provides,” says Teresa Walsh, global head of intelligence at FS-ISAC.

All eyes are now on regulators to see whether they will accommodate this new impetus.

“High-level support from regulators on the value of fighting future crime helps firms intuit that this type of information sharing is not only allowed, but expected to better protect customers,” Walsh adds.

When it comes to transactional data, too, regulators have a crucial role to play, says Bertrand Foing, CEO of Secretarium.

“Unless there’s a clear stand from the regulators and the ICO to allow management to share the entire set of pre-suspicious transactional data at scale, it’s going to be almost impossible to convince the private banks to do it. They can do it in the form of an experiment, pilots, or in some rare exceptions in a sandbox. But doing it as a private-private collaboration is not possible,” Foing says.

On that front, there is some good news. The US and UK governments published a statement in July 2022 announcing a joint innovation prize to stimulate developments in data sharing technology. Industry players hope this will herald the start of closer cooperation on the question of data sharing from a regulatory standpoint, too.

I could see them being adopted within a two- to three-year horizon. I think it’s going to move quickly. That’s partly because the UK and US governments are pushing for it. … It’s certainly not a technology problem—the technology is there

Mark Davies, Element22

Also in 2022, French regulator ACPR hosted a tech sprint in which 12 advanced confidential data pooling solutions were put to the test—including the technology designed by Secretarium and FutureFlow. In its summary report, ACPR concluded that PETs that enable data sharing “offer undeniable benefits in terms of security guarantees.”

Davies is upbeat on the outlook for PETs that enable data sharing between firms. “I could see them being adopted within a two- to three-year horizon. I think it’s going to move quickly. That’s partly because the UK and US governments are pushing for it. … It’s certainly not a technology problem—the technology is there,” he adds.

Realistically, financial crime is never going to go away. Nor will AML officers be put out of a job by automation. “You can have a recommendation engine advising you on the alerts that come up, but it will always be up to the human to decide how to action them,” Mainez says.

Now, PETs must make the leap from testing to implementation if they are to win widespread trust. If the technology can produce real-life results that are publicly validated by participants, Sobolevski believes, the banks will really pay attention.

Fifty years ago, we put two people on the moon’s surface with a computer the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. So we can fight financial crime together: we just need political willingness

Francisco Mainez, Lucinity

“In my estimation, even 20% of the banking system is sufficient to start producing meaningful results,” he says. “And the idea is that when you start producing meaningful results, that creates significant pressure for the others to join, because it becomes increasingly difficult for the holdouts to justify their case. “

Foing concurs, but adds that even data sharing between two institutions can have an outsized impact on identifying financial crimes. “Of course, the more the merrier, but it’s amazing the results you get with just two banks. The signals are up to 800% better,” he says.

For now, vendors in this area are watching keenly for a green light from financial institutions and authorities.

“I always say the same thing when it comes to technology,” Mainez says. “Fifty years ago, we put two people on the moon’s surface with a computer the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. So we can fight financial crime together: we just need political willingness.”

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Data Management

Stocks are sinking again. Are traders better prepared this time?

The IMD Wrap: The economic indicators aren’t good. But almost two decades after the credit crunch and financial crisis, the data and tools that will allow us to spot potential catastrophes are more accurate and widely available.

In data expansion plans, TMX Datalinx eyes AI for private data

After buying Wall Street Horizon in 2022, the Canadian exchange group’s data arm is looking to apply a similar playbook to other niche data areas, starting with private assets.

Saugata Saha pilots S&P’s way through data interoperability, AI

Saha, who was named president of S&P Global Market Intelligence last year, details how the company is looking at enterprise data and the success of its early investments in AI.

Data partnerships, outsourced trading, developer wins, Studio Ghibli, and more

The Waters Cooler: CME and Google Cloud reach second base, Visible Alpha settles in at S&P, and another overnight trading venue is approved in this week’s news round-up.

A new data analytics studio born from a large asset manager hits the market

Amundi Asset Management’s tech arm is commercializing a tool that has 500 users at the buy-side firm.

One year on, S&P makes Visible Alpha more visible

The data giant says its acquisition of Visible Alpha last May is enabling it to bring the smaller vendor’s data to a range of new audiences.

Accelerated clearing and settlement, private markets, the future of LSEG’s AIM market, and more

The Waters Cooler: Fitch touts AWS AI for developer productivity, Nasdaq expands tech deal with South American exchanges, National Australia Bank enlists TransFicc, and more in this week’s news roundup.

‘Barcodes’ for market data and how they’ll revolutionize contract compliance

The IMD Wrap: Several recent initiatives could ease arduous data audit and reporting processes. But they need buy-in from all parties if all parties are to benefit.